Helmet Streamers

During any total solar eclipse, you are guaranteed to see the magnificent solar corona extending far from the obscured solar disk. In general, the corona will not look like a smooth halo of light, but will have structure to it both big and small. The most dramatic large structures are the helmet streamers that look like their namesake and have been recorded in eclipse drawings since the 1800s.

During the Eclipse of Sept. 7, 1858 the French astronomer Emmanual Liais in Brazil rendered the corona with more distinct and detailed structure than earlier drawings. (The story of Eclipses, G. Chambers 1899) He identified an extended, smooth component onto which he superposed large, conical features along with some indication of prominences.

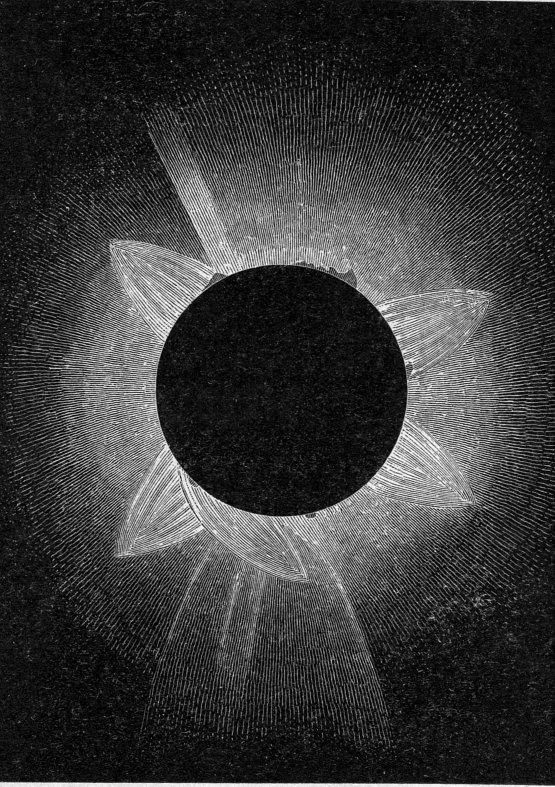

This astronomical drawing during the July 28, 1851 total solar eclipse was published in Thierry Moreux's 'Les Eclipses' and also shows pronounced conical-shaped features in a remarkably regular pattern.

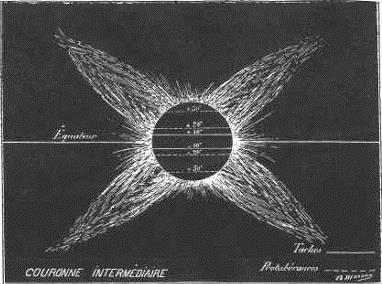

By the eclipse of July 29, 1878 Ettiene Trouvelot rendered this artist-quality painting of coronal details. Thanks to a cooperating sun with apparently a simpler countenance than before, the painting clearly and accurately showed two distinct components: the polar plumes resembling a toy bar magnet field, and two equatorial helmet streamers, along with a few prominences. Although photography was routinely in use by this time, Trouvelot insisted that they eye was far better at discerning details than a photograph.

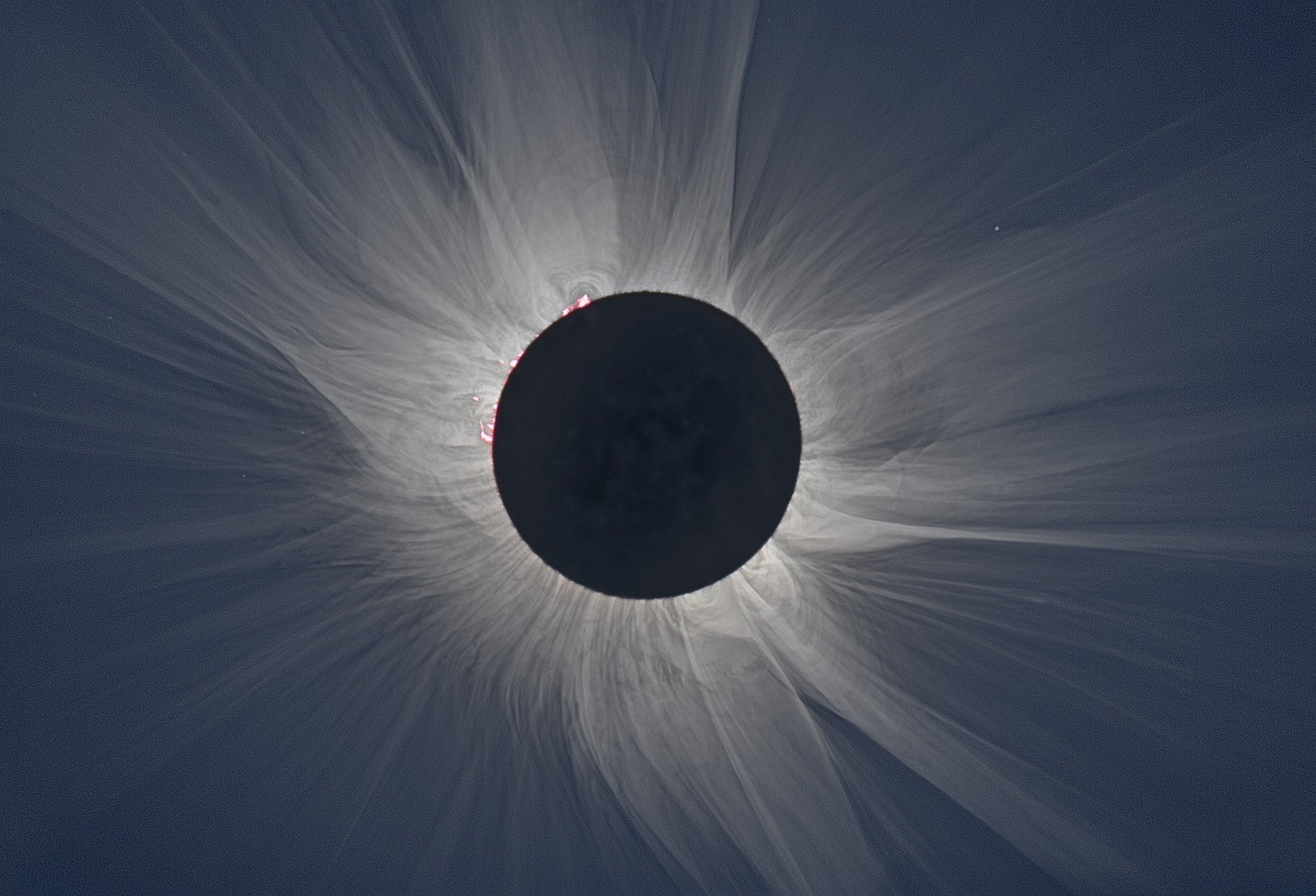

The conical, coronal features that were often seen during eclipses were eventually called helmet streamers, named after the spiked helmets popular during the late-1800s in Europe and elsewhere, especially in Prussia. Today we can capture details in these coronal features far superior to anything previously seen, as the following example shows.

So apart from a curious name, what are they, and how do they relate to other solar phenomena?

It has been known since the late-1800s that the coronal gases are very hot – in fact hotter than 1 million Celsius. This means that virtually all known elements are ionized and carry electrical charges, making this state a plasma. Moreover, based on the shapes of various sunspots and other details, magnetic fields play a big role in accounting for the appearance of the corona. This was borne out by direct measurements of sunspot magnetic fields by George Ellery Hale in 1906, and later direct measurements of coronal magnetic fields in the 1960s.

Helmet streamers get their shape from two phenomena: The first is that large active regions (sunspot groups) have magnetic fields that penetrate the chromosphere and can reconnect into large magnetic systems in the corona. The second phenomena is that the streamers eventually become sculpted by outflowing gas in the expanding corona or the solar wind, which draws them out into linear, radial features at a few million km from the solar surface.

Models of the magnetic fields in helmet streamers are created from observed corona measurements. Here is the predicted field model for the corona during the eclipse on December 4, 2002. Notice that many of the lines leave the solar surface and do not return, however the helmet streamer fields along the equator begin in one hemisphere and end in the other. This is a common field shape for the equatorial helmet streamers often seen and sketched during eclipses. (Credit: Jon Linker et al, Predictive Science Inc).

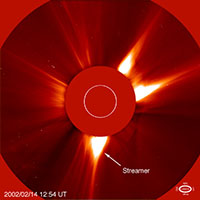

Coronal streamers can now be studied in detail even with no on-going solar eclipse thanks to spacecraft such as the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) with its LASCO instrument, which occults the bright solar disk and lets the fainter coronal structure be easily viewed. Here is an example of coronal streamers viewed on February 14, 2002. The white circle shows the size of the sun disk.